4-point control plan for managing heat stress in poultry

Climate change is driving increasing weather extremes, which has made heat stress more topical for UK poultry producers.

“Last year, some broiler operations lost up to 30% of their flock due to heat stress,” says St David’s Poultry Team vet Sean Wisdom.

“It was hot in anyone’s language; 40C is not normal.”

See also: How poultry unit manages heat stress with misting systems

Born and bred in South Africa, Sean qualified as a vet there and spent nine years consulting for broiler, broiler breeder and commercial layer operations throughout the country.

He is now based in the UK, and his experience of poultry production in a hot climate has become a valuable asset.

The industry is going to have to deal with higher temperatures for the foreseeable future, he stresses.

“If you want to be in poultry production for the next five to 30 years, you have to think about long-term management strategies.”

The catastrophic losses experienced last year grabbed headlines, but the subclinical performance losses from heat stress, such as decreased growth and egg production, probably hit farmers harder, he says.

“Where one farmer may have lost 30% of his broilers, 10 other farmers may have lost 50g of growth a bird, and that is very costly to the sector.”

Four aspects of control need to be considered: Long-term control, comprising investing and acting to manage risk; medium-term control being action in the period ahead of risk; short-term control, meaning action close up to risk period; and, critically, post heat-stress management.

1. Long-term control

House design

©Adobe Stock

Poultry houses in hot countries are designed to cope with heat – they are shaped for much greater ventilation capacity.

But it’s not feasible for established UK producers to just rebuild, says Sean.

“If a new site is going to be built, or there is a desire to reinvest by replacing old sheds or expanding a site, hotter temperatures and the house’s design and climate control system need to be a serious consideration.”

The cold hasn’t gone away, either, he adds.

“This is a particular challenge for UK producers. You can’t just build a farm to cope with hot weather; you’re also going to struggle with the cold.”

A greater temperature differential complicates house design.

“A cold winter’s day can easily be -5C to -10C. So, with the possibility of temperatures reaching 40C in the summer, the house has to cope with a temperature range of 50C. That’s challenging from an engineering perspective.”

Ventilation should also be factored in. “Make sure you can create longitudinal [tunnel] ventilation. This often means having a longer, thinner house than historically built in the UK,” he explains.

Insulation

Insulation is vital – it keeps heat in during cold weather and heat out during hot weather.

“In South Africa, we would advise producers to first look at their insulation to help with heat stress. If your houses aren’t well insulated, they will become ovens in the summer.”

Sean advocates buying the best insulation you can afford.

“Good insulation pays you back – it won’t just save on heating, it will also save on cooling.”

Ventilation

South African poultry operations have much greater ventilation capacities than in the UK.

Tunnel ventilation is best for maximising climate control, and should be included in new builds or retrofits – alongside sufficient fan capacity.

“Plan for the worst-case weather scenario and err on the side of extra fan capacity.

“The climate is only likely to get warmer, hence the need for greater fan capacity to deliver effective and efficient cooling.

“If you’re investing for the next 20-30 years, you want to make sure that investment delivers the solutions needed – now and well into the future.”

Cooling systems

Most cooling systems are based on evaporative cooling: misters or wet walls.

“There are advantages and disadvantages to both,” he says. “But an evaporative cooling system is important for any new build or retrofit.”

© Lubing Systems

Misting systems can be installed easily at both build and retrofit level, whereas wet walls are a more viable option for new builds.

“Retrofitting wet walls is a lot more difficult and costly,” he adds.

From a management perspective, misters require a little more input to avoid moisture accumulation in the shed.

Other systems such as air-conditioning are not practical on a commercial scale.

Estimated income losses in hot weather

Broilers

- Farm: Six houses each holding 30,000 birds

- Average price per kg: £1.10

- Growth loss per bird: 50g

- Lost income per house: £1,650 (£9,900 across six houses)

Layers

- Farm: 16,000-bird free-range unit

- Average price per dozen: £1.40

- Loss of saleable eggs through poor shell quality/depressed production: 5%

- Lost income per day: £92.40

2. Medium-term control

Stocking density

In South Africa, some broiler clients would decrease their stocking density in summer months by about 10%.

That’s not practical for a laying operation, but it could be a consideration for broilers.

Chickens generate a lot of heat, so fewer birds in a shed means less heat, less pressure on ventilation and more effective cooling.

“On an older site, where you can’t invest too much, taking a few birds out of production for one or two crops could reduce the most severe effects of heat stress.”

He acknowledges there are financial implications.

“Where capital can’t be invested, it might be worth considering what that 10% loss looks like in comparison to the 30% losses we’ve seen. It’s not a must-do, it’s about options.”

© Tim Scrivener

Nutrition

Nutritionists can help producers implement strategies to maintain bird performance during hot weather, but it needs to be planned two to three months ahead of likely heat stress conditions, perhaps in consultation with the farm vet.

Choices include different raw materials, particularly energy sources, which are critical for maintaining production when under stress.

How much should be invested?

New infrastructure may involve serious capital investment, as well as time and interruptions to production. So what’s the right level of outlay?

“The answer depends on multiple factors, looking at long-, medium-, and short-term controls,” says St David’s Poultry Team vet Sean Wisdom.

But one thing is clear: “We should expect to see further temperature increases as well as [more] days a year at those higher temperatures.”

This is all set against a backdrop of high feed and energy costs, as well as added pressure from labour challenges and the threat of avian influenza.

“If you chat with your vet and nutritionist, you can put together a sensible bird management and nutritional plan, and be in a better position to reap the benefits in terms of maintaining performance.

“That’s why it’s important to have a range of options, so producers can make the adjustments, improvements and investments that suit their birds and business needs.”

3. Short-term control

Power

Producers should prepare for hot weather a few days before it’s forecast.

“Start with your generator. It’s remarkable how often electricity supply maintains through the winter only to fail on the hottest day of the year,” he says.

“If you have mechanical ventilation and need all your fans running, that’s a big load on the generator, so make sure it’s performing as it should and you have enough diesel.”

House temperature

© Jason Bye

Mature layers and broilers more than 21 days old are at greater risk of heat stress, as their increasing size takes the house closer to capacity.

“If you have week-old broiler chicks, hot weather isn’t something to be as concerned about, but if you’re at 26 days then there are big concerns.”

Reducing temperature set points by 1-1.5C is worth considering for layers and broilers over 21 days in consultation with technical and veterinary advisers.

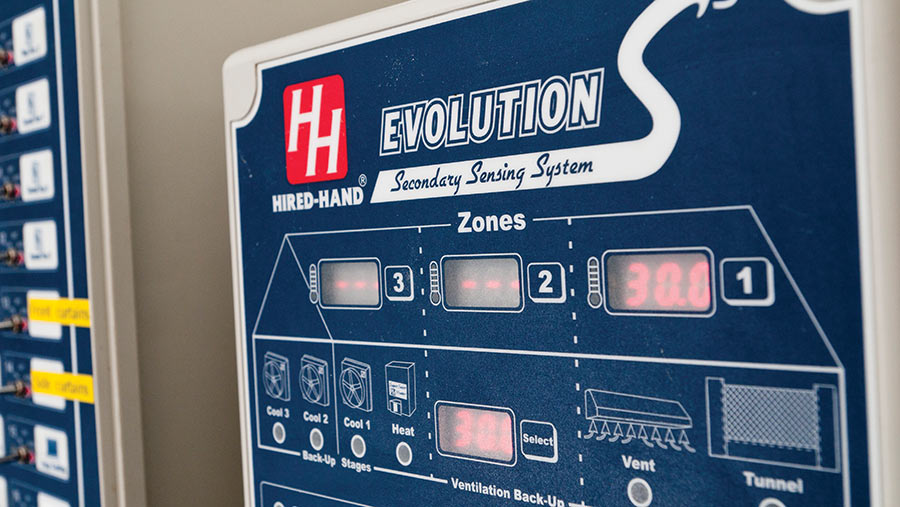

Humidity and climate control

High humidity compounds high temperatures, and making sure the house is as dry as possible will reduce humidity.

Remove wet bedding, and check drinkers and lines as well as puddles forming under ventilation inlets.

When temperatures increase, ensure the ventilation and cooling systems are working in synergy to maximise efficacy.

Electrolytes and water temperature

Another consideration is electrolyte supplements – specifically those containing sodium and potassium – to maintain bird hydration and performance. “These can be supplied by your vet,” Sean advises.

He suggests having two to three days’ worth of supplement to hand and knowing how much to use, though not starting until higher temperatures hit.

© Nicolae/Adobe Stock

Start them too soon and they will stimulate the birds to drink, he warns.

“If additional hydration is not needed at that point they will pass it in their droppings, which will raise the house moisture level – exactly what we’re trying to avoid.”

For producers who have a header tank system, another simple and effective way to cool water coming into the house is to freeze buckets of water and empty the ice blocks into the tank.

4. Post heat-stress management

Heat stress affects intestinal health in birds. “It’s prudent to anticipate problems after the risk period of heat stress,” he suggests.

“The two main options for supporting gut health in this period are organic acids and essential oils.

“You don’t want to invest in getting the birds through the hot period, for them to then develop nasty enteritis which causes performance loss and/or mortality.”