How to control gastrointestinal parasites in sheep and cattle

© Shutterstock/Iva-Vagnerova

© Shutterstock/Iva-Vagnerova Gastrointestinal (GI) parasites are major contributors to reduced ruminant productivity, and if left unmanaged or untreated, can have devastating effects on animal welfare and farm productivity.

Large populations of these GI nematodes can lead to a condition known as parasitic gastroenteritis in both cattle and sheep, which, as well as causing obvious clinical symptoms, can also causes sub-clinical disease in the form of reduced growth rates and poor carcass conformation.

Although this is often less dramatic in terms of its effect on the animal, the cost is usually far greater to the producer.

See also: Q&A: Complete guide to controlling worms in your herd

Emily Francis, veterinary surgeon at Westpoint Vets, picks out four key GI parasites in ruminants and highlights what exactly they are, how they affect animal health and what farmers can do to treat and prevent infections.

1. Nematodirus battus

What is it commonly known as?

Thin-necked intestinal worm.

What is it and how does it affect animal health?

Nematodirus battus is a round worm that lives in, and infects, the small intestines of lambs.

Unlike most parasitic worms, development of an infective larvae takes place within the egg, and hatching is delayed, so infection passes from one lamb crop to the next year’s.

Mass hatching usually happens after a frost, followed by warm weather, and if this hatching coincides with lambs starting to graze significant amounts of grass, it can cause death in the worst-case scenario.

What species are affected?

Sheep, goats and, occasionally, cattle.

What symptoms should I look out for?

Nematodirus can be difficult to diagnose, as there is not always a high egg worm count to go from, so it’s important to look out for key clinical signs, including dark brown scour, dehydration and, in the worst-case scenario, mortality.

What is the best way to treat and prevent cases on farm?

With diagnosis difficult, the best approach in terms of prevention is to use the Scops Nematodirus Forecast to determine risk-level and avoid lambs aged between five and 12 weeks grazing high-risk pastures.

The forecast predicts the hatch date for nematodirus based on temperature data from 140 weather stations throughout the UK, and should be used in combination with your grazing history to assess the risk of nematodirus infection in your lambs.

Coloured dots on the forecast map represent risk factor, with yellow representing low risk and black highlighting a very high risk.

It’s important to remember the hatch date also changes every year, so just because you’re not affected one year, does not mean you won’t be the following season.

Where cases of nematodirus are confirmed, farmers should treat infected lambs with a white drench. While there is lots of resistance to this type of treatment now, benzimidazoles remain the best remedy for this type of parasitic worm.

© Tim Scrivener

2. Teladorsagia circumcincta/Ostertagia ostertagi

What is it commonly known as?

Small brown stomach worm.

What is it and how does it affect animal health?

Teladorsagia circumcincta in sheep and Ostertagia ostertagi in cattle are both commonly known as a small brown stomach worm, and they invade and reproduce in the gastric glands of the abomasum.

This makes the animal’s glands thicken and not function as they should, in turn producing a chemical that reduces appetite and dramatically affects growth rates.

It also reduces the acidity of the stomach, which has a negative effect on protein digestion, so absorption is compromised.

Scops rules

When using anthelmintics you should always adhere to Sustainable Control of Parasites in Sheep (Scops) principles.

What species are affected?

Cattle, sheep and goats.

What symptoms should I look out for?

Due to the appetite suppression caused by the parasitic worm, the most common side effect is poor growth rates in youngstock and lambs. A low challenge can cause reduced growth rates of up to 30% that the animal may never recover from.

In older cattle, a drop in milk yield may also be a sign that there is a possible teladorsagia burden.

Due to the damage caused to the stomach, high burdens cause scouring, dehydration, weight loss and, in the worst-case scenario, death.

What is the best way to treat and prevent cases on farm?

Anthelmintic treatment should be used (group 1-5 for sheep and group 1-3 with cattle), but this should be decided in conjunction with a vet to incorporate individual farm resistance and pasture management factors.

In terms of prevention, this varies depending on the species. In sheep, faecal egg worm counts can be used to determine high burdens and then pasture rotation and good nutrition should be used to minimise risk.

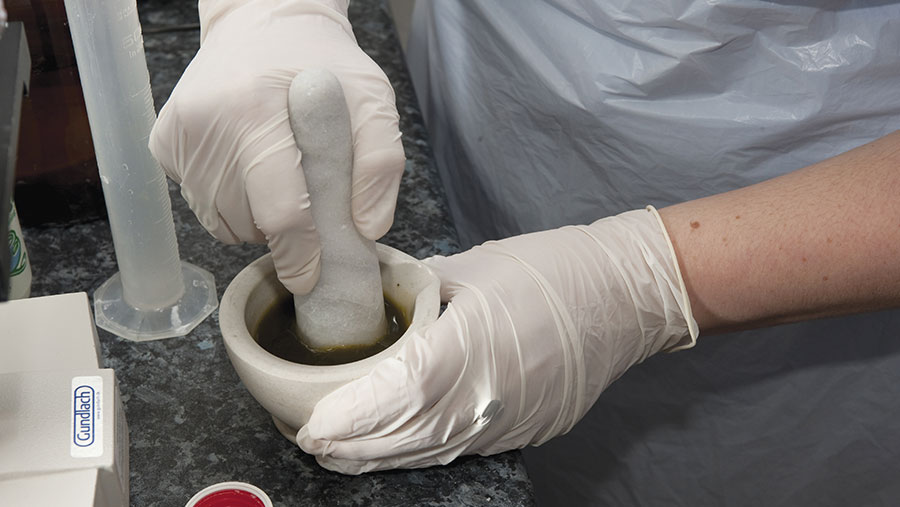

Carrying out faecal egg count in sheep faeces © FLPA/Shutterstock

In cattle, dung doesn’t tend to indicate the severity of the worm burden, so instead it’s safer to implement a preventative strategy that includes pasture rotation and targeted use of anthelmintics.

3. Haemonchus contortus

What is it commonly known as?

Barber’s pole worm.

What is it and how does it affect animal health?

Haemonchus contortus is a blood-sucking worm that lives and feeds off of the surface of the abomasum, causing severe anaemia and often death if not treated quickly.

What species are affected?

Sheep, goats, alpacas and occasionally cattle. Both adults and youngstock can be infected.

What symptoms should I look out for?

Clinical signs depend on the intake of worms. A large, quick intake shows itself via anaemia, pale mucus membrane and death, often following gathering of sheep. A slower intake often results in poor body condition, bottle jaw and poor milk yield.

What is the best way to treat and prevent cases on farm?

There is a range of suitable treatments for haemonchus infections. All five categories of anthelmintics, in addition to some flukicides, have efficacy.

However, there are some resistance issues to be aware of and this should be discussed with your vet.

Prevention is not so simple, unfortunately, as haemonchus populations are now appearing in the spring and summer, whereas previously it was only usually seen in the autumn. But a general prevention strategy can be helpful, and this includes avoiding the highest-risk pastures, monitoring egg counts and implementing pasture rotations where possible.

4. Cooperia curticei/Cooperia oncophora

What is it commonly known as?

Small intestinal worm.

What is it and how does it affect animal health?

Cooperia is a parasite that lives in the small intestine. While not as pathogenic as ostertagia, a combination of a cooperia and ostertagia infections can cause major issues.

Cooperia causes inflammation of the small intestine and affects the animal’s absorption of nutrients. When this is combined with inflammation of the stomach, the losses can’t be compensated for, meaning a much more severe type of infection is usually found.

What species are affected?

Sheep and goats (cooperia curticei) and cattle (cooperia oncophora).

What symptoms should I look out for?

Symptoms of cooperia are quite similar to those of ostertagia infections. They include loss of appetite, reduced body weight and condition and diarrhoea.

What is the best way to treat and prevent cases on farm?

Most animals gain immunity after one grazing season, but in the meantime, treatment can be provided with group 1-3 anthelmintics.

In terms of prevention, it’s important to practice good pasture management and monitor growth rates to spot any early signs of infections.