Practical tips on planning applications when diversifying land

© Collins Photography/Adobe Stock

© Collins Photography/Adobe Stock Alternative enterprises can open up new sources of revenue while using redundant or surplus buildings, or by making better use of parcels of less productive land.

They can also be a way to add value to assets or create jobs – often forming part of a wider strategy to help bring the next generation into the business.

One of the first steps when considering a project should be to assess the planning considerations and the options available.

When can you use permitted development rights?

Shannon Fuller, a planner at land agents Robinson & Hall, says it is important if you are considering using existing buildings to understand at an early stage whether full planning permission for change of use will be required or whether permitted development rights (PDRs) apply.

See also: So you want to…offer caravan storage?

The benefit of using PDRs to diversify is that, theoretically, it is a simpler, quicker and cheaper way to get the project through the planning system.

PDRs give landowners the rights to make certain changes to a building without the need to apply for full planning permission.

They derive from a general planning permission granted by Parliament, rather than from permission granted by a local planning authority (LPA).

Instead of submitting a full planning application, a prior approval notification is made to the planning authority of an intent to develop within the terms of the legislation.

The rights of landowners with regard to PDRs are set down by the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) Order 2015 (GPDO), which includes the following classes focusing on the change of use in agricultural buildings:

- Class Q: Enables the conversion of agricultural buildings to up to five new dwellings, the floor space is limited at 465sq m and the structure of the building must be confirmed as capable for conversion. You also must be able to evidence that the building was previously used for agriculture on or before 20 March 2013.

- Class R: Enables the conversion of agricultural buildings of up to 500sq m to a flexible commercial use. This can cover diversifications into shops, restaurants, cafes, office space, and storage and distribution. The building must have been last used for agriculture on or before 3 July 2012.

- Class S: Enables the conversion of agricultural buildings to state-funded schools or registered nurseries, providing the building was used for agriculture on or before 20 March 2013 and the change of use does not exceed 500sq m.

When can you not use PDRs?

There are restrictions on when PDRs are available, which include the dates establishing when the buildings must have been in agricultural use.

If a site is located within a National Park, area of outstanding natural beauty or conservation area then Class Q rights will not be available, but Class R rights will be.

Changes to listed buildings, or buildings within the curtilage of a listed building, will always need full planning permission and listed building consent.

How does the process work?

The local authority has 56 days from receipt of the application for prior approval to make its decision on the application.

Under Classes Q and R, if the LPA has not responded within 56 days, the development can proceed – providing there are no outstanding issues with the proposals and no objections such as a highways objection, which would mean it did not meet the criteria set out within the GPDO legislation.

In some cases, planning officers will request extensions to the 56-day period, but applicants are not obliged to agree.

Any PDR pitfalls to avoid?

One error that people sometimes make is that they are not aware they cannot use PDRs retrospectively, warns Mrs Fuller.

“If a development has been undertaken without submitting a prior approval application, the business must seek full planning permission retrospectively.”

Class Q rights cover the change of use and the works necessary, but for Class R, it is key to note that the PDR only permits the change of use for the building.

Any operational works to then enable the change of use will require planning permission, she adds.

This means, for example, if you have the Class R approval to open a farm shop in a redundant agricultural building, any works you might need to do to make it fit for purpose – for example, building extra walls or changing doorways – would need planning permission.

Farmers also need to be aware that there is a relationship between Class Q rights and Class A rights (under Part 6 of the GPDO) to put up a new agricultural building. So if a new building is put up under Class A, then Class Q rights will be revoked for 10 years and vice versa.

Top tips for making a successful planning application

Shelley Jones, an associate director and planner with rural diversification specialist Rural Solutions, says while local planning officers are perhaps more supportive of planning applications for rural diversification than in the past, the devil will often be in the detail of individual applications.

Understanding the types of application that a local authority is likely to support – and whether there may be sensitivities – is therefore important.

Local context

“While national policy guidance is quite supportive of diversification, every area will have its own local policy and that can be more restrictive,” she says.

Local plans that set out the local policies are published on the local council’s website.

Alternatively, a professional adviser can be helpful in guiding an applicant through the process and will also help to reduce the risks of failing to supply the right information at the right time.

Most local authorities offer a pre-application advice service where you can talk or write to a planning officer about your ideas and get some feedback.

This gives applicants an early indication of whether an application is likely to be successful and guidance on any technical matters that will need to be addressed. Fees can vary considerably depending on the local authority.

Supporting material

Common mistakes when seeking planning permission include a lack of supporting material, particularly around some of the technical requirements, such as an ecology survey, traffic study or a structural report on the building. This can lead to objections to an application based on the missing information.

Planning advisers will usually have experience of what a particular planning authority would expect to see with an application, so this early engagement can help reduce this risk.

Time and scale

Timing should also be considered. Generally, surveys for protected species will need to be carried out in the spring and summer months, so applicants may need to wait while the required information is collected.

The scale of development may also be worth considering when putting together an initial application, particularly where it may be for a new enterprise.

“I think there can be a fear among some planning authorities, particularly where an application involves applying for new buildings, if the diversification is a completely new venture.

“If the venture fails then they will end up with new buildings in the countryside where they might not have normally allowed them.

“Sometimes starting small and utilising redundant buildings to get something established can be better than going in with the full proposals at the beginning,” says Mrs Jones.

She points out that planning, to a degree, is a political process, in that decisions are often taken by a planning committee rather than a planning officer.

While members will be basing their decisions on planning policies, they will also be mindful of local objections.

“Taking time to engage and communicate your plans with the local community ahead of an application going in can be worthwhile in terms of helping to quell opposition,” says Mrs Jones.

Can you expect a quick response?

Patience is likely to be required. There are backlogs in many planning departments because of a shortage of experienced planning officers to process applications.

Many planning applications go beyond the initial eight-week determination period, often stretching to 12-16 weeks or beyond.

“The view across the industry is that planning application numbers have gone up during the pandemic, while staff numbers have not, so there are lots of areas where there is a bottleneck,” warns Mrs Jones.

Shepherd’s huts and holiday cottage

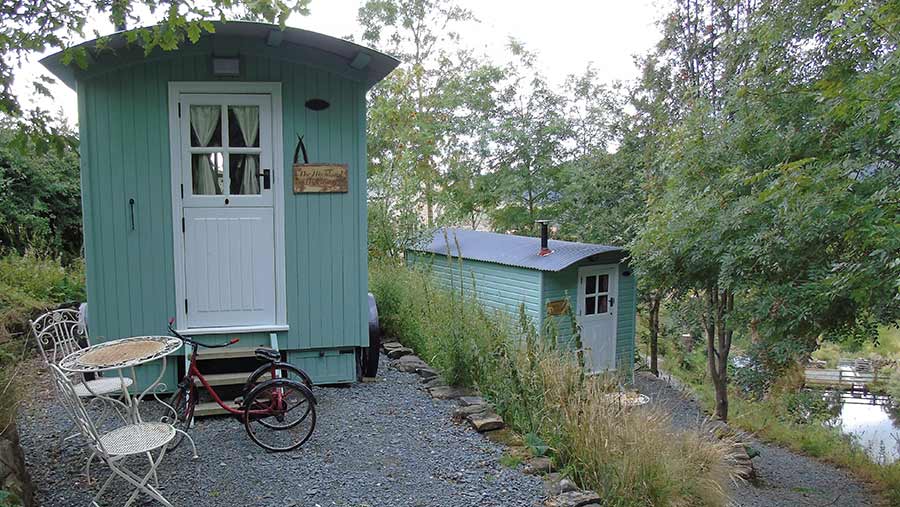

Securing planning permission for five glamping-style shepherd’s huts, followed by the provision of a new holiday cottage converted from a former workshop, has allowed one client of consultant Rural Solutions to develop an additional income stream to support their traditional farming activities.

The application to locate the shepherd’s huts in a wooded valley was quite sensitive as it was in an area of outstanding natural beauty and on a biodiverse farm.

© Rural Solutions

“The client noted that it was a funny thing that having planted most of the trees and developed the wildlife habits themselves, the improvement work made the application more difficult in some respects,” says Mrs Jones.

“We also had to be prepared for questions on the increased demand on our spring water supply and sewage disposal system.”

There were some objections locally, including from the town council and a few questions from the planning office, nevertheless planning permission was granted first time.

Lettings have gone well and the feedback was good, so the farm went on to apply for permission to convert the farm garage and workshop into a holiday cottage.

The building had no particular architectural merit, and the change of use was somewhat speculative. However, as a conversion of an existing building, rather than the development of new buildings, the new holiday cottage has not had any additional visual impact upon the landscape setting.

“Everything depended on the presentation of a good case up front. Happily, there were no objections, and it went straight through, and planning permission was granted.”